Abstract

Nine out of 10 people breathe air that does not meet World Health Organization pollution limits. Air pollutants include gasses and particulate matter and collectively are responsible for ~8 million annual deaths. Particulate matter is the most dangerous form of air pollution, causing inflammatory and oxidative tissue damage. A deeper understanding of the physiological effects of particulate matter is needed for effective disease prevention and treatment. This review will summarize the impact of particulate matter on physiological systems, and where possible will refer to apposite epidemiological and toxicological studies. By discussing a broad cross-section of available data, we hope this review appeals to a wide readership and provides some insight on the impacts of particulate matter on human health.

Particulate Matter

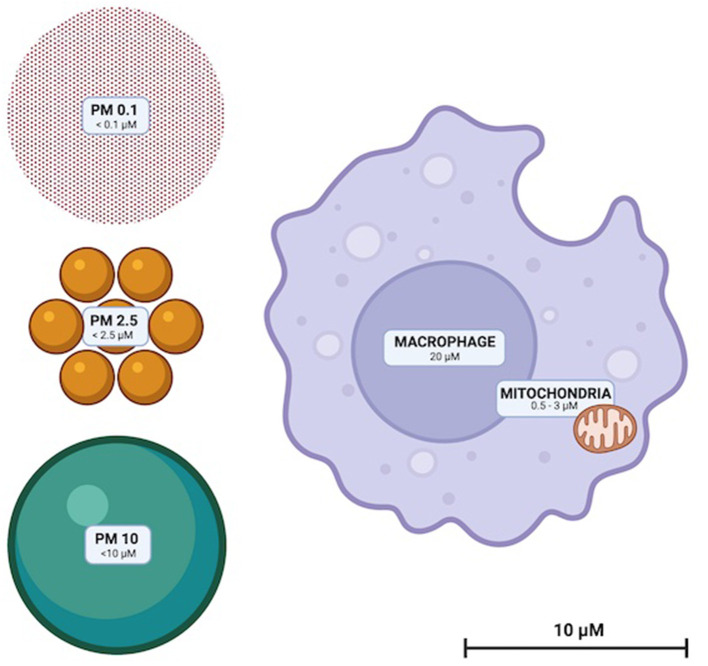

Particulate matter (PM) are solid compounds suspended in air that are sufficiently small to be inhaled (Figure 1). PM is categorized by particle diameter (measured in μm); PM0.1, PM2.5 and PM10 whilst ambient concentration is usually quantified as μg/m3. Some PM are of natural origin (bushfires, dust, sea spray, aerosols, etc.) but anthropogenic PM (diesel, coal and biomass combustion and emissions from metal refineries etc.) are the most dangerous to health (13). High atmospheric concentrations of human-made PM, and toxic and oxidative chemical characteristics render them disproportionately hazardous (13). Elemental and complex chemical species of PM are diverse, with surface shape, chemistry and charge impacted by emission source and environmental conditions. PM chemistry can change through reactions with other airborne PM and be affected by the oxidative effects of ozone and low ambient pH (14, 15).

Figure 1.

To scale illustration of the relative sizes of PM10, PM2.5, and PM0.1. Representative macrophage and mitochondria are included to scale for

Renal Disease

Human kidneys filter ~180 L of blood each day and are therefore vulnerable to PM exposure (21, 72).

In people, PM2.5 exposure has been linked to an accelerated decline in glomerular filtration rate,

diminished glomerular function during pregnancy, increased risks of chronic kidney disease, end stage renal disease, renal failure and chronic kidney disease mortality (72–74).

Human studies have also revealed that PM2.5 exposure to positively correlate with risk of albuminuria; a marker of glomerular disfunction (72).

A comparison of renal biomarkers in welders and office workers revealed that

welders - exposed to much higher levels of PM2.5 that office worker controls –

had elevated plasma markers of renal tubule damage; urinary kidney injury molecule-1 and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (75).

Another study investigating the potential for tubule damage in humans revealed a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 exposure to be associated with increased nephritis hospital admissions (76).

PM2.5 exposure is associated with an elevated risk of adverse post kidney transplant outcomes, including acute rejection, graft failure and death (73, 74).

A study specifically investigating the impact of PM on post-transplant outcomes found a 10 μg/m3 increase of PM2.5 to correlate with a 1.31-fold increase in the odds

of transplant failure, a 1.59-fold increase in

odds of delayed graft function and a 1.15-fold increase in all-cause mortality within 1 year of surgery (77).

A similar study revealed an increase of 1 μg/m3 in PM10 exposure to be associated with increased risk of biopsy proven rejection, graft failure and mortality (78).

Intratracheal exposure of PM2.5 to immunodeficient mice revealed no obvious renal histopathology. However, PM exposure was associated with elevated serum markers of renal damage including kidney injury molecule-1, cystatin C and uric acid. Moreover, 14-day PM exposure progressively increased renal concentrations of malondialdehyde, hydrogen peroxide, glutathione peroxidase, nuclear factor kappa-β, tumor necrosis factor-α, transcription factor protein-65, NADPH oxidase 4 and heme oxygenase-1 (79).

In rats, sub-chronic exposure of PM2.5 resulted in elevated plasma β-2-microglobulin and cystatin-C; serum markers of early-stage kidney damage (80–82).

PM exposure has also been found to induce histopathological lung damage, increase median blood pressure, increase urine volume and water consumption (80–82).

Exposure of rats to diesel emission PM significantly reduced renal blood flow in controls and to a greater extent in rats with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease (81).

Similar work in a mouse model of adenine-induced CKD revealed that PM exposure elevated renal tumor necrosis factor-α, lipid peroxidation, reactive oxygen species, collagen deposition, necrotic cell counts, dilated tubules cast formation and collapsing glomeruli (49).